As Tropical Plant lovers, we’ve spent years growing 60+ Anthurium crystallinum in different indoor environments—from bright lofts to low-light apartments—experimenting with substrates, humidity strategies, grow tents, and propagation methods. This guide distills everything we’ve learned into a practical care reference you can rely on, especially if you’re growing indoors in North America or Europe.

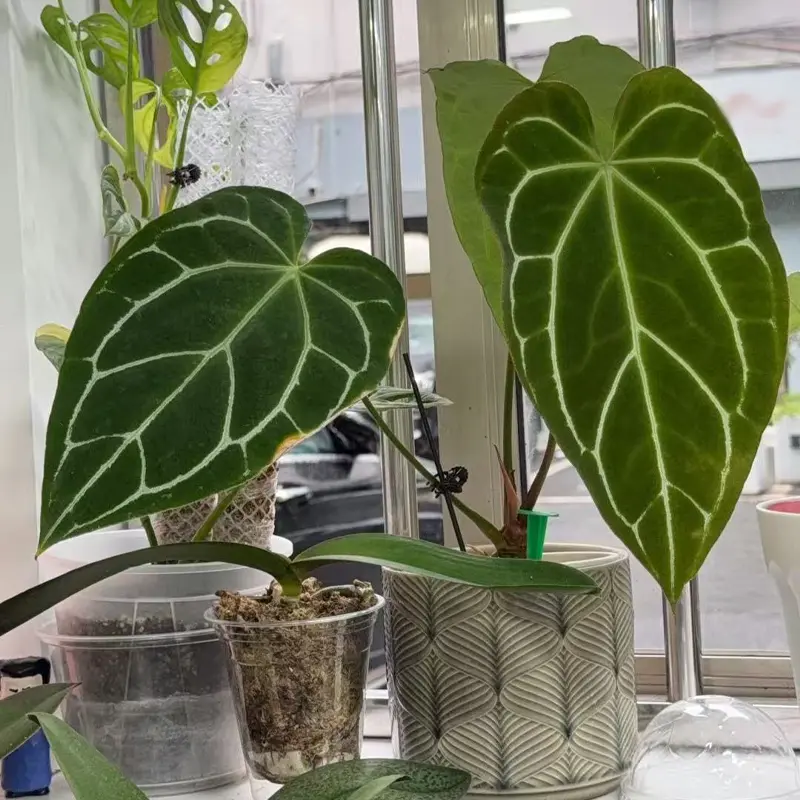

Anthurium crystallinum is one of the most iconic velvet-leaf aroids: oversized, heart-shaped foliage, sharply defined silver veins, and a soft texture that feels almost unreal. Despite its exotic appearance, it’s not difficult when the basic needs—light, humidity, substrate, and airflow—are met.

This guide reorganizes everything from the beginning:

Where crystallinum comes from, why it looks the way it does, how hybrid lines emerged, and why colors like red venation or red emergent leaves appear—before we move into the complete, expert-level care instructions.

Plant Profile: What is Anthurium Crystallinum?

- Botanical name: Anthurium crystallinum

- Family: Araceae

- Origin: Colombia, Peru, Central America, Ecuador,Panama

- Growth habit: Epiphytic or terrestrial aroid

- Leaf texture: Velvety (“velutinous”) with dramatic white venation

- Mature leaf size: 20–60 cm (depending on genetics and environment)

It grows as both:

- Epiphytic (on tree trunks with roots gripping bark)

- Terrestrial (on humus-rich forest floors)

This image displays a healthy specimen of Anthurium crystallinum, a tropical perennial admired for its spectacular foliage rather than its blooms. The plant features large, heart-shaped, velvety leaves in a deep green hue, marked by striking, contrasting silvery-white veins that radiate across the surface, while several characteristic inflorescences—long, pale spadices on slender stalks—rise above the leaves. Native to the rainforest margins from Panama down to Peru, this member of the Araceae family is treasured for its ornamental value. While collecting existed previously, Anthurium crystallinum gained significant traction as an indoor houseplant in the United States and Canada during the “aroid boom” of the 2010s, shifting from a rare specialist item to a highly sought-after, more widely available staple in the North American plant market by the early 2020s.

Why hobbyists love it

- Easily hybridized and widely available due to tissue culture advancements.

- The velvety sheen reflects light in a way that looks almost metallic.

- Fast leaf enlargement with proper humidity and feeding.

Key environmental traits of its habitat

- Dappled canopy light (never full sun)

- High air humidity (70–90%)

- Gentle airflow

- Spongy, organic substrate rich in decayed plant matter

Historical Context: From Wild Species to Cultivar Market

Anthurium crystallinum was formally described in the late 19th century by Belgian botanist Jean Jules Linden after collectors brought specimens to Europe during the orchid/aroid boom of that era.

The species immediately caught attention because of:

- Its velvety leaf surface (velutinous texture)

- Striking silver primary and secondary veins

- Large heart-shaped leaves

By the early 20th century, crystallinum was already used in hybridization programs in Europe.

Rise of Tissue Culture (TC) Lines

In the 1990s–2000s, tissue culture labs in Europe and Southeast Asia began mass-producing crystallinum. TC lines introduced:

- More uniform leaf shape

- Faster growth

- Stable venation patterns

- New coloration traits (silver, dark, red emergent forms)

This explains why today’s crystallinum in plant shops often looks different from historical wild forms.

Why Crystallinum Looks the Way It Does (Botanical Morphology)

Velvety Leaf Surface (Velutinous Layer)

The characteristic velvety texture is caused by:

- Microscopic, light-scattering trichomes

- Dense epidermal layers developed to reduce moisture loss

This reflects light, giving the “metallic glow.”

Silver Venation

The white/silver veins come from air pockets beneath the epidermis that refract reflected light.

The stronger the contrast:

- The more genetically pronounced the venation

- The better the lighting and nutrition

- The more mature the plant

Leaf Size Potential

A mature crystallinum leaf can reach 40–60 cm indoors, and over 80 cm in its natural habitat.

Variations, Color Forms & Why Some Crystallinums Show Red Veins

Wild populations show wide variation in:

- Leaf shape (rounder, narrower, elongated)

- Vein thickness

- Stem color

- Leaf emergent color (green, bronze, red)

Red Veins vs Silver Veins

Many growers notice that some crystallinum have:

- Red veins

- Bronze new leaves

- Pinkish petioles

Why does this occur?

It is caused by differences in anthocyanin pigments, influenced by:

- Genetics — Certain lines naturally produce anthocyanins.

- Light levels — More LED or bright light increases red pigmentation.

- Nutrient availability — Higher phosphorus or magnesium can intensify red tones.

- Plant maturity — Younger or new leaves often have anthocyanin flush.

So yes—red venation is normal in some crystallinum lines and not a sign of hybridization alone.

Red Emergent Leaves Or Even Purple

Many crystallinum produce:

- Deep red,purple or bronze emerging foliage

- Leaves that fade to green over 1–2 weeks

This trait is selected in modern TC lines because of its high popularity among collectors.

Hybrids: Crystallinum’s Most Influential Crosses

Crystallinum is one of the most common parent plants in velvet-leaf hybrid programs.

Common Hybrids

(1) Anthurium magnificum × crystallinum

- Thicker, more leathery leaves

- Stronger venation and compact growth

- Easier for beginners

(2) A. forgetii × crystallinum

- Rounder leaves

- No sinus (top gap) if forgetii genes dominate

- Silky velvet texture

(3) Crystallinum Silver Blush

- Very bright silver veins

- More tolerant of low humidity

- Anthurium varieties with more silver veins usually grow more slowly.

(4) Red/Purple Stem Lines

- Anthocyanin-rich

- Produce red emergent leaves

- Popular among modern growers

- The color of the anthurium with its red and purple veins will fade in summer.

Why Hybrids Exist

- To produce stronger, more resilient indoor plants

- To introduce new sheen or coloration

- To increase leaf size

- To improve pest resistance

Crystallinum hybrids often outperform the pure species when humidity is low or when grown under LEDs—useful information for many indoor hobbyists.

Anthurium Crystallinum Care Guide

Caring for Anthurium crystallinum becomes much easier once you understand what kind of plant it is and why its needs differ from the typical houseplants found in nurseries. the plant carries the full set of traits shared across the Araceae family. These traits—epiphytic roots, humidity-sensitive leaves, and a strong preference for oxygen-rich substrates—shape every aspect of how the plant reacts inside a home. When growers understand these biological habits, the plant stops being “difficult” and starts behaving predictably.

Araceae Characteristics That Affect Care

- Epiphytic or semi-epiphytic roots Designed for air, not dense soil. They absorb humidity and oxygen simultaneously.

- Velvety, thin foliage Higher humidity requirement than leather-leaf species.

- Aerial roots that climb The plant expands best when given a pole or “something to touch.”

- Slow-rooting but fast-leaf sizing Root health matters more than fertilizer strength.

- Moist forest environment origin Moisture consistency > heavy watering.

Light sets the pace of growth, but humidity determines leaf quality. Crystallinum performs best in bright, filtered light, similar to what it would receive under a forest canopy. Too little light results in elongated petioles and muted venation; too much sun washes out the velvet texture and can create yellow patches. Grow lights work extremely well for crystallinum, especially when placed 60–90 cm above the canopy, where the light is strong enough to stimulate growth but gentle enough to preserve pigment.

Humidity between 70–85% is ideal. At these levels, new leaves emerge glossy, full, and symmetrical. When humidity drops below 50%, growth slows and newly unfurling leaves often develop hard edges, creases, or partial crisping. Unlike calatheas—which also enjoy high humidity but tolerate finer soils—crystallinum needs humidity paired with airflow. Without circulating air, moisture clings to the velvety leaves and increases the risk of fungal spotting. A small fan running at a low constant speed is often enough to maintain the right balance.

Temperature is generally straightforward: 18–26°C keeps the plant in its comfort zone. Chilly nights below 15°C cause slower growth and, occasionally, leaf deformation. High temperatures above 30°C are tolerable only when humidity and airflow are both strong.

Watering: Stable Moisture Without Stagnation

Watering is the most misunderstood aspect of crystallinum care because the plant does not tolerate extremes. If the substrate dries fully, the fine roots desiccate and new leaves may emerge with brown margins or distorted lobes. If the substrate becomes waterlogged, oxygen disappears from the root zone and rot sets in surprisingly fast.

The ideal approach is to water when the top two to three centimeters feel slightly dry but the pot still retains some internal moisture. A well-structured substrate allows this equilibrium naturally. Clear pots help tremendously for beginners, as crystalinum roots visibly indicate their condition: firm white or yellow roots signal good health, while brown, mushy, or hollow roots suggest overwatering or compaction.

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| New leaf edges brown before fully unfurling | Low humidity or uneven moisture | The leaf dehydrated during expansion |

| Yellowing from oldest leaf upward | Overwatering or substrate breakdown | Root oxygenation is impaired |

| Dull, matte foliage | Insufficient light | Increase brightness without adding direct sun |

| Crisping at leaf tips | Low humidity or fertilizer salt buildup | Increase humidity and flush soil |

Substrate: The Foundation of Healthy Roots

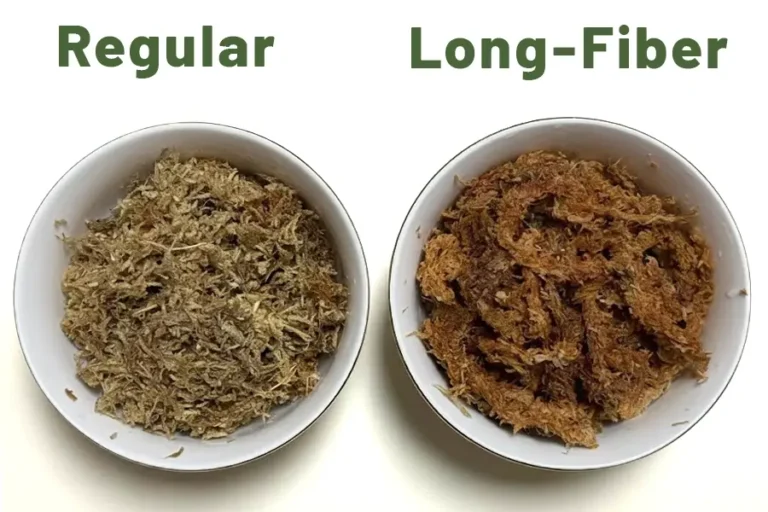

A proper aroid mix is essential. Most growers rely on a combination of orchid bark, perlite or pumice, sphagnum moss, and a small amount of organic matter such as worm castings. This composition mimics the porous forest floor where anthuriums naturally root. Bark and pumice provide structure and airflow, moss holds moisture without compacting, and castings offer gentle nutrients without the salt accumulation associated with synthetic fertilizers.

The key is that the substrate should feel light, airy, and springy—even when moist. A substrate that becomes heavy, muddy, or uniformly dense cannot support the plant’s oxygen-hungry root system. Repotting every 8–12 months maintains this structure because bark naturally decomposes over time. Many experienced growers take this opportunity to examine the root system, trim away older roots, and “refresh” the mix to keep the plant vigorous.

Airflow, Pests, and the Role of Environment

Crystallinum’s velvety leaves attract thrips and spider mites more readily than leathery species like Monstera. The fine surface traps dust and moisture, creating micro-habitats that pests enjoy. Regular gentle airflow keeps leaves dry and discourages insects from settling. It also reduces fungal risk when growing in high humidity setups such as greenhouse cabinets.

Routine leaf cleaning with a soft brush or microfiber cloth preserves the plant’s ability to photosynthesize through its fine trichomes—something many growers overlook. Clean leaves not only look better but grow faster.

Fertilization and Growth Behavior

Crystallinum responds best to light but regular feeding. High nitrogen fertilizers can cause overextension of petioles, while overly strong fertilizers can burn delicate roots. Diluted liquid fertilizers every two to three weeks during active growth maintain a steady nutrient supply. Slow-release pellets can be incorporated into the substrate for consistent background nutrition.

Growth occurs through a rhythmic pattern: a new leaf emerges, expands, hardens, and then the plant rests briefly before pushing the next leaf. Under excellent conditions, this cycle repeats every four to six weeks. When humidity, light, or substrate conditions falter, this cycle slows dramatically.

Creating an Environment the Plant Understands

Ultimately, growing crystallinum well indoors is less about following strict rules and more about translating its forest habits into a home setting. It wants light that mimics filtered canopy sunlight, humidity reminiscent of misty understories, and soil that behaves like decomposing organic matter layered with bark and roots. Once these environmental cues align, crystallinum becomes unexpectedly stable and generous—producing larger, brighter, and more deeply veined leaves with each growth cycle.

Light Table

| Light Level | Effect on Plant |

|---|---|

| Bright Indirect (ideal) | Thick veins, larger leaves |

| Low Light | Leggy petioles, smaller leaves |

| Direct Harsh Sun | Burned patches, fading color |

Humidity Table

| Humidity % | Growth Behavior |

|---|---|

| 40–50% | Just surviving, small leaves |

| 60–70% | Healthy indoor growth |

| 70–85% | Best coloration, best leaf size |

| >90% | High risk of fungus unless airflow added |

Watering Table

| Condition | What It Means | What To Do |

|---|---|---|

| Leaves curl slightly | Mild underwatering | Water thoroughly |

| Yellow bottom leaves | Overwatering | Improve drainage, reduce frequency |

| Brown edges on new leaf | Inconsistent moisture or low humidity | Increase humidity & stabilize watering |

Soil & Repotting

This plant needs airy, breathable soil with good water-holding capacity.

Ideal aroid substrate

- 30% orchid bark or coco chips

- 30% perlite or pumice

- 20% sphagnum moss

- 10% charcoal

- 10% worm castings

Why this works

- Bark + perlite → oxygen

- Moss → even moisture

- Charcoal → absorb impurities

- Castings → gentle nutrition

Soil Comparison Table

| Soil Type | Good / Bad for Crystallinum | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Aroid mix (ideal) | Excellent | Mimics epiphytic conditions |

| Succulent mix | Terrible | Dries too fast; roots desiccate |

| Peat-heavy potting mix | Risky | Retains moisture but lacks airflow |

| Pure sphagnum | Good for rooting, not long-term | Holds moisture but compacts over time |

Fertilizer Table

| Season | Feeding Frequency | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Spring–Summer | Every 2–3 weeks | Most active growth |

| Fall | Once a month | Adjust to decreased light |

| Winter | Optional | Only if under grow lights |

Support: Moss Pole vs No Support

Crystallinum grows more impressively with support.

Benefits of a moist moss pole

- Larger leaves

- Shorter internodes

- Faster root growth

- Better hydration for aerial roots

Quick Overview Table (All Care Factors)

| Care Category | Ideal Requirement | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Light | Bright, filtered | Avoid harsh afternoon sun |

| Humidity | 70–85% | Strongest factor for leaf size |

| Watering | Even moisture | Never bone dry |

| Soil | Aroid mix | Airy, chunky, moisture-retentive |

| Temperature | 18–26°C | Avoid sudden drops |

| Fertilizer | Light & consistent | Every 2–3 weeks |

| Airflow | Gentle, continuous | Prevents fungus & pests |

| Support | Moss pole optional | Helps aerial roots climb |

Reference List For Further Reading

Formatted in APA-style with accessible online sources.

1. Boyce, P. C. (1998). Anthurium (Araceae) species descriptions & ecology.

Royal Botanic Garden Kew – Aroid botanical archives.

2. Croat, T. B. (1983). A revision of the genus Anthurium (Araceae) of Mexico and Central America.

Missouri Botanical Garden Press (MoBot).

https://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/default.asp

3. Croat, T. B. & Ortiz, O. O. (2020). Araceae taxonomy and species notes.

Missouri Botanical Garden – Aroid Research Resources.

https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org

4. Exotic Rainforest (2008–2024). Anthurium crystallinum species profile & cultivation notes.

A well-documented aroid specialist resource.

http://www.exoticrainforest.com

5. International Aroid Society. (n.d.). Aroid care principles, environmental needs, and species information.

6. Madison, M. (1977). A revision of the genus Anthurium Section Cardiolonchium.

Harvard Papers in Botany – PDF at JSTOR.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41761224

7. Royal Horticultural Society (RHS). (2024). Anthurium indoor care guidelines.

https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/anthurium

8. Garcia, N. (2019). Aroids of the Rainforest: Ecological requirements & growth behavior.

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI).

9. University of Florida IFAS Extension. (2022). Aroids: physiology, humidity tolerances, and substrate aeration.

10. Orchid Bark & Epiphyte Substrate Studies. (2014–2022).

American Orchid Society – substrate aeration and moisture-holding research (relevant for epiphytic aroids).

11. Houseplant Resource Center (2021). Understanding velvety-leaved aroids and trichome function.

https://houseplantresourcecenter.com

12. Botanical Review Articles on Anthocyanins (for red emergent leaves).

Harvard University Herbaria – pigment and anthocyanin physiology.

13. Kew Science – Plants of the World Online. (2024). Anthurium crystallinum profile & distribution map.

https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:86792-1

14. Flora of Panama / Flora Mesoamericana Project.

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.