If you’ve ever bought a new houseplant or garden ornamental and noticed a small line on the label that reads “Propagation Prohibited” or “Asexual Reproduction Not Allowed,” you’re not alone. Many plant lovers pause at that moment, wondering whether something as simple as taking a cutting could really be illegal. It feels counterintuitive. After all, propagation is one of the oldest and most joyful parts of gardening. You nurture a single plant, help it multiply, share it with friends, and feel a quiet pride in seeing it thrive.

Yet the reality is that in many countries, propagating certain plants is restricted—sometimes mildly, sometimes strictly. These restrictions can come from several different legal systems layered on top of one another: intellectual property protection for new cultivars, national wildlife and conservation laws, bans on invasive species, and even regulations related to controlled substances. For the everyday gardener, these rules can be confusing, especially when they vary so much by region and are rarely explained clearly at the point of purchase.

This guide brings all of these threads together into a single, coherent explanation. It unpacks how “propagation” is defined legally, why plant patents exist, how endangered and invasive species laws factor into gardening, what counts as illegal propagation, and what practical steps gardeners can take to stay safe, ethical, and well-informed.

Although the topic is complex, the essence is simple: owning a plant does not always mean you own the right to copy it. Understanding why is the key to navigating modern gardening responsibly.

Table of Contents

Understanding “Propagation”: Legal Meaning vs. Gardening Meaning

Gardeners usually use the word “propagation” casually to mean growing more plants—whether that’s dividing a perennial, rooting a cutting, germinating seeds, or rescuing an accidental offset. But the legal meaning is narrower and far more precise.

In horticulture, propagation includes both sexual reproduction (growing from seed) and asexual reproduction (making clones). In law, however, most regulations specifically target asexual propagation. This is because asexual reproduction produces genetically identical copies, which is exactly what plant patents and breeders’ rights aim to control.

The difference matters. Plant patents almost never cover seedlings, because sexual reproduction creates variation. But asexual methods—cuttings, grafting, division, tissue culture, bulb scaling—produce exact replicas of the original plant. From the legal perspective, that replica is considered a “copy.” So even if it comes from a small piece you rooted in a jar of water, it falls under the same definition.

A helpful comparison is to think of buying a book. You own the physical object you purchased. But you do not gain the right to print thousands of identical copies. Similarly, buying a plant gives you ownership of that plant, but not necessarily the right to multiply the variety itself. That right may belong to someone else.

Why Plant Patents and Plant Variety Rights Restrict Propagation

Most home gardeners first encounter propagation restrictions because the plant they purchased is a patented cultivar or a variety protected under plant breeders’ rights (PBR/PVP). These systems exist in many countries and aim to protect the work of breeders who spend years developing new varieties.

To make this easier to digest, here’s a quick reference table summarizing how different intellectual property protections work:

Table 1. Common Forms of Plant Intellectual Property Protection

| Protection Type | Covers | What It Restricts | Duration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Patent (US) | Asexually reproduced new varieties | Cuttings, division, grafting, tissue culture | ~20 years | Does not cover seeds; no personal-use exemption |

| Plant Variety Protection (PVP/PVPA) | Seed-propagated or tuber crops | Seed production, tuber propagation | ~20–25 years | Managed by USDA or national PVP office |

| Plant Breeder’s Rights (EU/UK/AU etc.) | Asexual and sexual reproduction | All commercial propagation | 20–30 years | Equivalent to PVP in other regions |

| Utility Patent (US) | Genetic traits or methods | Very broad restrictions | 20 years | Can cover GM traits or breeding processes |

| Trademark | Plant’s marketing name | Use of name in commerce | Renewable | Trademark ≠ patent; variety may be unprotected but name not usable |

Intellectual property protections are the source of the most common propagation bans seen on plant tags. They exist for a simple economic reason: breeding new plants is slow, expensive and risky. Breeders spend years selecting, stabilizing, and testing new cultivars. Without legal protection, anyone could buy a single plant, propagate hundreds of clones, and sell them while contributing nothing to the research that created them.

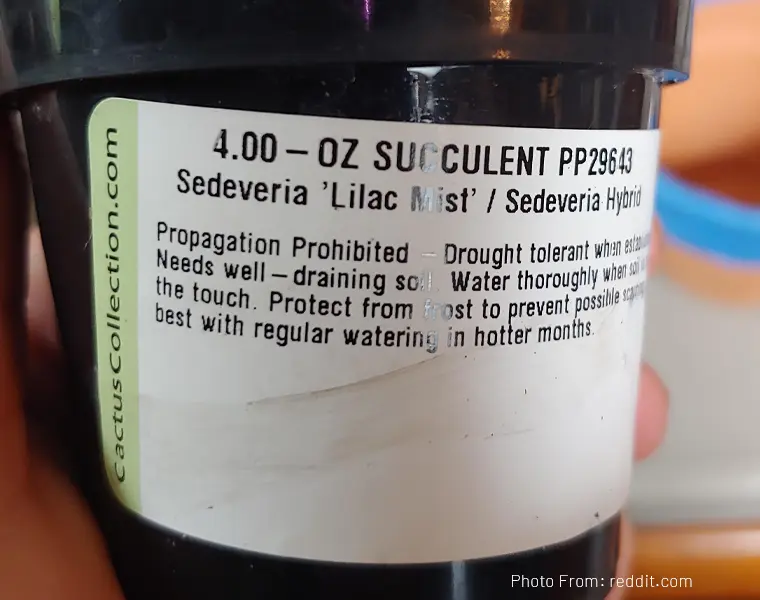

This is why labels often include abbreviations like:

- PP# (Plant Patent number)

- PPAF (Plant Patent Applied For)

- PBR (Plant Breeder’s Right)

- PVP (Plant Variety Protection)

- Unauthorized Propagation Prohibited

- Asexual Reproduction Prohibited

Even though these warnings are usually aimed at commercial growers, the law often applies equally to hobbyists. There is no “personal-use exemption” written into plant patent law. Enforcement tends to focus on nurseries selling unlicensed plants, not individuals with a single extra cutting—but legally, the principle is the same: a patented plant cannot be cloned without permission.

This relationship between breeders and growers is also why many companies track unauthorized propagation actively. Specialized organizations monitor online sales, inspect commercial nurseries, and even pursue legal claims when unlicensed cuttings are found. In several cases involving roses and branded ornamental plants, fines have reached hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Endangered Plants, Wildlife Laws, and the Ethics of Conservation

Propagation restrictions aren’t always about protecting breeders. In many cases, they exist to protect the plants themselves. Around the world, thousands of species are threatened by habitat loss, climate change and poaching. Many succulents, orchids, cycads, and carnivorous plants have been stripped from the wild because collectors wanted rare specimens.

To counter this, most countries have national endangered species laws, and many participate in the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). These laws regulate the harvesting, possession, transport, and sale of protected plants. Some species cannot be traded at all; others require special permits, even if artificially propagated.

The problem becomes clearer if you trace what often happens in the rare plant market:

- Plants are illegally harvested from the wild.

- They enter black-market supply chains.

- They are propagated in nurseries without documentation.

- They eventually appear online as “rare exotics,” often mislabeled as “nursery grown.”

By the time a hobbyist buys one, it looks completely legitimate. But the original wild populations may be collapsing.

The Conophytum crisis in southern Africa is one striking example. As demand from collectors surged online, populations were stripped bare, sometimes overnight. Authorities have since arrested smugglers, seized shipments, and cracked down on illegal propagation and transport. But demand still fuels the trade.

For gardeners, the safest approach is simple:

If a plant is very rare, high-priced, or labeled “wild collected,” treat it with extreme caution. Propagating it may be illegal, but more importantly—it may be unethical.

Invasive Species and the Hidden Risks of Propagation

At the opposite end of the spectrum are plants that are too successful. Invasive species can overwhelm native ecosystems, damage agriculture, clog waterways, and cost governments billions in control measures. For this reason, many countries and states have strict laws prohibiting:

- selling invasive plants

- transporting them

- intentionally planting them

- propagating them in any form

For gardeners, these laws often appear in unexpected ways. A plant that seems harmless in one region might be tightly controlled in another. For example, purple loosestrife is admired by many gardeners but banned in several US states because it outcompetes native wetland species. Water hyacinth is a popular pond plant but is illegal in multiple regions because it forms massive floating mats that disrupt waterways.

Propagation comes into play because even a single cutting, bulb or fragment can start a new infestation. Many invasive species spread not by seed but by vegetative pieces. A gardener dividing a plant or sharing a root section with a friend may unknowingly introduce it into a new ecosystem.

Biosecurity rules add yet another layer. Organizations like USDA-APHIS in the United States or national plant health authorities in Europe regulate the movement of soil, plants with roots, and plant material across borders. A cutting ordered online might carry a pest that does not exist in your region. Even if the species itself is harmless, the associated pests are not.

To make this easier to visualize, here is a simple table summarizing how invasive and biosecurity restrictions overlap:

Table 2. Why Some Plants Are Restricted Even If They Aren’t “Rare”

| Risk Category | What Triggers It | Why Propagation Matters | Example Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive Species | Plant spreads aggressively in local ecosystem | A single cutting can start an infestation | Japanese knotweed, water hyacinth |

| Biosecurity Risks | Plant or soil may carry pests/diseases | Propagation and movement spread contaminants | Scale insects, nematodes, fungal pathogens |

| Illegal Import Risks | Plant imported without phytosanitary permits | Propagated offspring remain illegal | Online succulent trade, soil contamination |

These rules may feel restrictive, but they exist for important ecological reasons. Invasive species can spread silently for years before anyone notices, and once they take hold, eradication is extremely difficult. Understanding these risks helps gardeners avoid accidentally contributing to long-term environmental damage.

Controlled Substances and Toxic Plants: The Rarest Category

A smaller but noteworthy category involves plants regulated because of their chemical properties. Some species contain psychoactive compounds or toxic alkaloids and are therefore controlled under drug or poison laws. These plants are not typically found in mainstream gardening, but occasional confusion arises when ornamental varieties overlap with species targeted in drug legislation.

In most places, these rules regulate possession, cultivation, or extraction more than propagation itself. But because propagation is part of cultivation, the effect is similar: you cannot legally multiply the plant.

For the average gardener, the takeaway is simply to research unfamiliar plants before growing them—especially anything known for medicinal, hallucinogenic, or toxic properties.

What Counts as Illegal Propagation? The Boundaries Explained

A common misconception is that propagation is only illegal when done for profit. But plant protection laws do not distinguish between personal and commercial use. The legal question is not why you propagated the plant but whether you reproduced a protected variety without permission. In practice, enforcement focuses on nurseries, online sellers and large-scale operations, yet the underlying rule still applies to everyone.

To clarify the difference between legal and illegal methods, here is a concise table:

Table 3. Propagation Methods and Their Legal Status on Protected Plants

| Method | Legal Status for Protected Plants | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cuttings (stem, leaf, node) | Illegal | Counts as asexual reproduction |

| Division / pups / offsets | Illegal | Produces genetic clones |

| Air layering | Illegal | Still creates a clone |

| Root cuttings | Illegal | Same genetic material |

| Tissue culture | Illegal | Commercial labs require licenses |

| Seeds (sexual reproduction) | Usually legal | But PVP/PVPA or contracts may restrict seed use |

| Accidental growth (self-offset) | Legal to possess | Illegal to intentionally reproduce |

The key idea is that any intentional act to create a clone violates a patent or breeders’ right unless licensed. In the case of endangered or invasive species, the restriction may apply to both seeds and clones.

Real-World Cases: How Propagation Laws Are Enforced

Propagation laws become more real when you see actual cases. Several high-profile legal actions illustrate how seriously these issues are taken.

In the ornamental plant industry, several growers have been fined for unauthorized propagation of well-known varieties such as the ‘Knock Out’ rose series and various Proven Winners cultivars. These cases typically involve nurseries taking their own cuttings instead of buying licensed stock. Fines can be calculated per unauthorized plant, turning even small breaches into expensive mistakes.

Another example is the global conversation around “proplifting,” where people collect fallen leaves or broken stems from garden centers or public spaces. While often framed as harmless, proplifting can constitute theft, and if the plant is patented, propagating the pieces can also be an intellectual property violation.

Meanwhile, at the opposite end of the spectrum, succulent poaching in South Africa and Namibia has become a major criminal issue. Entire hillsides of Conophytum have been stripped by smugglers. Propagation in this context is part of a global black-market chain. Enforcement has intensified, involving international cooperation, undercover operations, and strict penalties.

Finally, invasive species legislation has led to “Cease the Sale” and “Cease the Propagation” orders in several US states, forbidding nurseries and homeowners from reproducing or distributing certain plants known to damage ecosystems. These laws aim to reduce long-term ecological and economic harm.

How Gardeners Can Stay Safe, Ethical, and Compliant

Despite the complexity of the topic, gardeners can avoid problems with just a few thoughtful habits.

1. Always read tags carefully.

If a plant includes abbreviations like PP#, PPAF, PBR, or PVP—or explicitly warns that propagation is prohibited—treat that seriously.

2. Understand where your plant came from.

If a plant is rare, unusually expensive, or advertised as “wild collected,” propagation may be illegal or unethical. Supporting legitimate nurseries helps protect native populations.

3. Avoid taking unpermitted cuttings.

Whether in a shop, a botanical garden, or a public park, fallen pieces are not automatically free for the taking. They may belong to someone else or come from a protected variety.

4. Prefer public-domain or heirloom varieties if you enjoy propagating.

These plants are legally safe to share, clone, and pass down.

5. Be aware of local invasive species rules.

A plant that seems harmless may be banned in your region. Growing or sharing it could cause ecological damage.

6. For small shops or bloggers, establish a compliance routine.

Keep records, verify plant rights before selling, and learn the import/export rules for plant material.

Ethics Beyond the Law: The Heart of Responsible Gardening

While the law provides a framework, ethics often go further. Even when illegal propagation seems low-risk, it undermines the work of breeders and can distort the horticultural economy. Conversely, buying rare wild plants from questionable sources may harm ecosystems even if it is technically legal in your region.

Asking “Can I legally propagate this?” is already a sign of thoughtful gardening. Asking “Should I?” is even more important. The best gardeners consider the long-term health of both cultivated and wild plant communities.

Propagation is a joy—but joy is always richer when paired with responsibility.

FAQ: Common Questions About Illegal Plant Propagation

Is it really illegal to propagate a patented plant for personal use?

Yes. Plant patents usually do not include personal-use exemptions. Enforcement targets businesses, but the law applies to everyone.

How do I check whether my plant is protected?

Examine the tag for PP#, PPAF, PBR or PVP markings. If in doubt, search national plant patent databases (e.g., USPTO, PVPO) or ask the nursery.

Are seeds exempt from plant patents?

Plant patents normally only cover asexual propagation, but PVP and contracts can restrict seed use. Always read the packaging or seller’s terms.

Can I take a fallen leaf or broken stem from a store?

No. It may still be considered property of the store, and propagating protected varieties is illegal regardless of how you obtained the piece.

Is swapping cuttings with friends allowed?

Only if the plant is not protected. Swapping protected varieties still counts as unauthorized propagation.

What happens when a plant patent expires?

The variety enters the public domain and can be propagated freely, although trademarked brand names remain protected.

Are all rare plants illegal to propagate?

No. Rarity is not the same as legal restriction. Only protected, endangered, or invasively regulated plants are affected.

Can I protect a plant I discovered myself?

Yes. If it is truly new, distinct, stable, and non-obvious, you can apply for a plant patent or breeder’s right.

Do these rules apply globally?

Most developed countries have similar systems (often harmonized under UPOV), but details vary. Always check local laws.

What should bloggers or sellers include in disclaimers?

Clarify that content is educational, not legal advice. Encourage readers to check local regulations and emphasize that your business uses legally sourced propagation material.

Conclusion: Why These Rules Matter

Propagation restrictions exist for three interconnected reasons: to protect breeders’ intellectual property, to conserve endangered plants and prevent destructive poaching, and to stop invasive species and pests from spreading. Although the rules can feel complicated, they reflect a larger effort to balance human enjoyment of plants with scientific innovation and environmental responsibility.

For gardeners, the path forward is simple: stay curious, stay informed, and when in doubt—ask. Legal and ethical propagation is not only possible, but deeply satisfying. In choosing the right plants to multiply and share, you contribute to a healthier horticultural world, one cutting at a time.

References

- Beaury, E. M., Patrick, M., & Bradley, B. A. (2021). Invaders for sale: The ongoing spread of invasive species by the plant trade industry. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 19(10), 550–558. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2392

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. (2022). Preliminary guidance on terms related to the artificial propagation of CITES-regulated plants. https://cites.org

- Schmidt, E. (2022, January 20). Propagation prohibited? Understanding plant patent protection. University of Cincinnati Law Review Blog. https://uclawreview.org/2022/01/20/propagation-prohibited-understanding-plant-patent-protection

- United States Code. (2024). 7 U.S.C. § 2541: Infringement of plant variety protection. Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/7/2541

- United States Patent and Trademark Office. (n.d.). General information about 35 U.S.C. 161 plant patents. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://www.uspto.gov/patents/basics/types-patent-applications/plant-patent-application

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. (n.d.). Plant Variety Protection Office. https://www.ams.usda.gov/services/plant-variety-protection

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. (n.d.). Plant Protection and Quarantine. https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/ppq-program-overview

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. (n.d.). Laws and regulations to protect endangered plants. https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/Rare_Plants/conservation/lawsandregulations.shtml

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Endangered Species Act: Overview. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.fws.gov/law/endangered-species-act

- VanZandt, N. (2023, March 8). Propagating plants and intellectual property. The Hardwick Gazette. https://hardwickgazette.org/2023/03/08/propagating-plants-and-intellectual-property

- Whitacre, B. (2024, November 25). Propagating your plants might be illegal—Here’s what you should know. Better Homes & Gardens. https://www.bhg.com/what-is-a-plant-patent-6823149

- Potts, L. (2023, April 19). The controversial plant propagation hack that has gardeners divided. Better Homes & Gardens. https://www.bhg.com/controversial-plant-propagation-hack-7486632

- European Commission. (2021). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the experience gained from the application of the plant passport system pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2016/2031 (COM(2021) 787). https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/7e89c9e6-9920-493a-a777-bb1e67075ecc_en

- Plant Heritage. (n.d.). Plant legislation and plant passports. Plant Heritage. https://www.plantheritage.org.uk/conservation/conservation-cultivation-advice/plant-legislation

- Welz, A. (2025, March 6). A craze for tiny plants is driving a poaching crisis in South Africa. Yale Environment 360. https://e360.yale.edu/features/south-africa-plant-poaching

- Maron, D. F. (2022, March 8). These tiny succulents are under siege from international crime rings. National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/tiny-succulents-are-under-siege-from-international-crime-rings

- Mark, M. (2025, January 24). The rise of plant poaching: How a craze for succulents is driving a new illegal trade. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/13af6c1a-9854-4420-9c15-673895c2ded3

- National Invasive Species Information Center. (2021, August 9). Invasive plants are still for sale as garden ornamentals, research shows. U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/resource/12059

- Conservation International. (2025, March 10). News spotlight: A unique poaching crisis takes root in South Africa. Conservation News. https://www.conservation.org/news/news-spotlight-a-unique-poaching-crisis-takes-root-in-south-africa

- Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. (2022). Harnessing technology to end the illegal trade in succulent plants. https://www.kew.org/science/our-science/projects/technology-illegal-trade-succulents